The story of Louie Louie is a more interesting one than anyone would guess. Even sticking to the most basic facts, which Dave Marsh rarely does, the twisted lineage of this tune is as strange a tale as any in American folklore.

The basic facts are as follows. Richard Berry writes the lyrics backstage while working with The Rivera Bros, and hearing them perform Rene Touzet's "El Loco Cha Cha," the intro of which supplies the central riff and beat to the song. The lyrics are inspired by Chuck Berry's "Havana Moon" and Johnny Mercer's "One More for the Road," although Marsh notes that Nat "King" Cole's "Calypso Blues," which inspired "Havana Moon," is actually closer lyrically to Louie. The chorus most likely is inspired by the chant of "Louie, Louie, Louie" in Louie Jordan's "Run, Joe." Berry's version (with The Pharoahs) is released in 1957 on the B-side of "You Are My Sunshine." It's a hit on the West Coast, but never breaks nationally. In 1959, Berry sells the publishing rights to the forgotten, out-of-print song, depriving himself of a steady income over the next 3 decades, until he wins the rights back in an early-90's lawsuit.

Meanwhile, Ron Holden and the Playboys begin including the song in their live sets as they play throughout the Pacific Northwest. "Rockin'" Robin Roberts and The Wailers record the first rock version around 1960, adding the "Let's give it to 'em right now!" and the guitar solo which both The Kingsmen and Paul Revere and the Raiders steal note-for-note. The Wailers' version isn't a hit, but the upcoming Northwest garage bands all include it in their repetoir. The flashy local heroes Paul Revere and the Raiders record it the same week, in the same studio, as the amateurish garage band The Kingsmen. the Raiders' version sounds like a slicker version of the Wailers', but the Kingsmen's version has a straighter rock beat, dropping the rest at the end of the 5-note riff (they didn't have a copy of the record to reference), and a grungier sound.

Marsh's account of the Kingsmen session is hysterical. The mic is on some kind of boom, so that the singer has to yell up to it. They do a piss-take just to get warmed up, and the producer tapes it and decide it's good enough to use. Marsh swears you can hear the drummer say "fuck!" as he screws up near the end of the guitar solo. He also later claims that Keith Moon stole his entire drum style from the fuckups on the Kingsmen recording.

Both versions are making dents in the charts in different regions, but ultimately it is the Kingsmen's version that breaks big. And the reason for it's popularity seems to be inherintly linked to the unintelligibility of the vocals.

There's plenty of intrigue and comedy in the story of The Kingsmen's rise to stardom, but the best part of the book, by far, deals with the FBI investigation of the song. This central chapter is at once a fascinating study of the viral spread of an urban myth, and a wickedly funny satire of authority in 1960's America. Shortly after the Kingsmen record hit, kids began circulating pages with the "real" lyrics written on them, a more-or-less meaningless string of sexual references that seemed to be written by people with no sexual experience. These lyrics can be heard, the legend says, when the 45 is played at 33 1/3, or, in other versions, are "audible to anyone who

really pays attention, a conspiratorial touch worthy of Foucault's Pendulum". Discovered by concerned parents and teachers, these lyrics were promptly reported to the FBI in Minneapolis, Tampa, Detroit, all over the nation. The FBI spent 2 1/2 years investigating this without, Marsh points out, ever even considering the possibility that the lyrics WEREN'T dirty! No satirist could make this stuff up! They spent hours listening to the record at various speeds, trying to determine the lyrics, and found them unintelligible, but "The lyrics are only impossible to learn if you're willfully trying to hear what's not there."

Here is the FBI at their most brililant: We don't know what we're dealing with, and it seems to be gibberish, but that gibberish must be presumed guilty until all rampantly paranoid parents and teachers stop believing the fantasies of teenagers suffering from hormonal overload.The Detroit beurau is particularly tenacious with their attempts to silence the subversive rock song, which Marsh suggests creates the "Instant Karma" that produces MC5, a real-life Communist Revolutionary Rock Band.

Marsh even waxes philosophical about what the dirty lyrics meant to their generation: "Somebody, somewhere, came up with the idea that Louie Louie had dirty lyrics not only as a way of putting on other kids and panicking authority, but as a way of creating something that rock n roll needed: a secret as rich and ridiculous as the sounds themselves."

Marsh writes in an appropriately silly style, but never downplays the importance of the story. He gets a couple facts wrong near the end: Henry Rollins didn't sing on Black Flag's "Louie Louie" (not even the version stuck on the end of later pressings of Damaged--it's Dez Cadenza on vocals), and The Beach Boys sing on the Fatboys' version of "Wipe Out," not "The Twist." But he gets the idea right, and traces the three chords through rock history from the 50's through the 90's. You get a nice, detailed portrait of various obscure rock scenes--Los Angeles doo-wop, Pacific Northwest garage bands--and a fascinating tour of the ins-and-outs of the record industry. All in about 200 pages.

Here's one of my favorite versions, from

The Best of Louie Louie, Vol. 2. It's by The Angels, most famous for "My Boyfriend's Back." I love the way they stretch out the words, "Louie Lou-I-A, Lou-ou-I-A, HEY!," and I love how the "Oh!" at the end of the first chorus gradually becomes a much more suggestive "Ugh!" by the end.

The Angels - Louie, LouieAnd what the hell, here's Paul Revere's version. Not as good as the Kingsmen's, but it still rocks.

Paul Revere and the Raiders - Louie, LouieLouie Louie by Dave Marsh

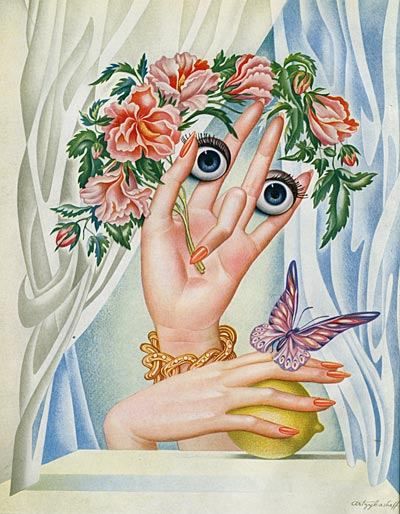

More great pics in the article. And in case you missed it, last week's L.A. Weekly has a typically great piece of writing by

More great pics in the article. And in case you missed it, last week's L.A. Weekly has a typically great piece of writing by